This post is authored by Andrew Goldberg, ACRA Chief Lobbyist.

On November 12, President-elect Trump announced the formation of a Department of Government Efficiency, or “DOGE,” that would be tasked with delivering a “smaller Government, with more efficiency and less bureaucracy” by the nation’s 250th anniversary in July 2026.

Trump further announced that Tesla/SpaceX CEO Elon Musk and former Presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy would head the DOGE.

Neither the Trump transition team nor the DOGE leaders have released a lot of details about how the DOGE will work. But because both Musk and Ramaswamy have in the past expressed ambitious goals for shrinking the size of the federal government, the DOGE announcement has created a lot of public interest about what it can and cannot do.

This report outlines what it known to date about the DOGE and how it may impact the operations and funding of the federal government.

DOGE Overview

It is important to note that, despite its name, the Department of Government Efficiency is not an official government agency. It will act more as an outside, independent commission. As a result, it will have no direct ability to effect changes in federal laws, rules, funding or personnel decisions. Those will remain with Congress and the Executive Branch.

That said, by nature of the fact it was formed by the incoming President, and considering that a number of members of Congress have expressed enthusiasm over the DOGE, we expect its recommendations will carry weight with policymakers in the next two years.

Of particular note is that House Republicans announced shortly after DOGE’s unveiling the formation of a DOGE subcommittee of the House Government Reform and Oversight Committee, to be headed by Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA)[i], and the formation of DOGE caucuses in both the House and Senate[ii]; while the caucuses are predominantly Republican, at least one Democratic House member has joined.[iii]

Musk and Ramaswamy have yet to provide a lot of details about how the DOGE will work but offered a window into their thinking in a November 20 Wall Street Journal op-ed[iv]. They suggested that their three main areas of work would be in cutting regulations, reducing the size of government (i.e., the workforce), and cutting spending.

They also noted that they plan to work primarily through executive action, as opposed to seeking legislative changes.

They took particular aim at the federal regulatory framework and the personnel who run it: “Most legal edicts aren’t laws enacted by Congress but ‘rules and regulations’ promulgated by unelected bureaucrats—tens of thousands of them each year. Most government enforcement decisions and discretionary expenditures aren’t made by the democratically elected president or even his political appointees but by millions of unelected, unappointed civil servants within government agencies who view themselves as immune from firing thanks to civil-service protections.”[i]

They also indicated that they are “assisting the Trump transition team to identify and hire a lean team of small-government crusaders, including some of the sharpest technical and legal minds in America.” This team, they wrote, will work with the new administration closely, while Musk and Ramaswamy will “advise DOGE at every step.”[ii]

Potential Impacts of the DOGE

The DOGE’s potential impacts to the federal government fall into three broad categories: policymaking (i.e., laws, regulations, executive actions); spending; and personnel.

Policymaking

As noted above, the DOGE does not have the authority to enact changes in federal laws (the domain of Congress) or regulations and executive actions (the jurisdiction of the White House and federal agencies). That said, the DOGE can propose policy changes that its backers in Congress and the new administration could attempt to enact.

It is common for a new president to attempt to undo many of the regulations his predecessor put in place – and in fact, President Biden revoked numerous regulations that President-elect Trump instituted in his first term.

Regardless of the DOGE’s existence, it is expected that Trump will attempt to unwind Biden-era rules on hot-topic items like climate, diversity, workforce protections and health care. Under the Administrative Procedures Act, the administration must follow a deliberative process in proposing and issuing new regulations; that will not change.

Furthermore, it is expected that President-elect Trump will take executive actions in an attempt to fulfill campaign promises on issues including tariffs and deportations of undocumented immigrants. Some of these may face court challenges, but this is not uncommon (recall how Biden’s initial student debt forgiveness plan was struck down by the Supreme Court).

Where the DOGE may have an impact is if they recommend broader changes to the regulatory system. In their op-ed, Musk and Ramaswamy said they hope to take advantage of recent Supreme Court rulings that limited federal agencies’ ability to issue regulations without clear congressional intent:

“DOGE will work with legal experts embedded in government agencies, aided by advanced technology, to apply these rulings to federal regulations enacted by such agencies. DOGE will present this list of regulations to President Trump, who can, by executive action, immediately pause the enforcement of those regulations and initiate the process for review and rescission. This would liberate individuals and businesses from illicit regulations never passed by Congress and stimulate the U.S. economy.”[i]

It is not clear whether a President could – as Musk and Ramaswamy want Trump to do – pause enforcement of regulations via executive action without going through the traditional rulemaking process.[ii] Musk and Ramaswamy assert in their op-ed that, while “[t]he use of executive orders to substitute for lawmaking by adding burdensome new rules is a constitutional affront,” using executive orders “to roll back regulations that wrongly bypassed Congress is legitimate and necessary to comply with the Supreme Court’s recent mandates.” Ultimately, it may be up to the courts to decide.

Spending

Both Musk and Ramaswamy have called for massive reductions in the amount of federal spending. Musk has promised to cut $2 trillion from the $6.5 trillion annual federal budget, although he has not specified if that is in a single year or over multiple years. During his presidential campaign, Ramaswamy proposed eliminating the Education Department, the FBI and the IRS.

Federal spending is generally divided into three buckets:

- Mandatory spending. This bucket is monies that the government is obligated to spend pursuant to law and not subject to annual congressional appropriations. It includes the major entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security. The amount spent by government on these programs each year depends upon the level of need or demand.

- Discretionary spending. This bucket is what is commonly referred to as appropriations. It is funding that Congress allocates each year for a wide range of federal programs; federal agencies cannot spend beyond what they are appropriated unless Congress passes supplemental appropriations. Discretionary spending is normally categories a either defense (i.e., military and national security) and non-defense (everything else).

- Debt Interest. This constitutes payments on the national debt, which must by law be paid and cannot be changed or reduced.

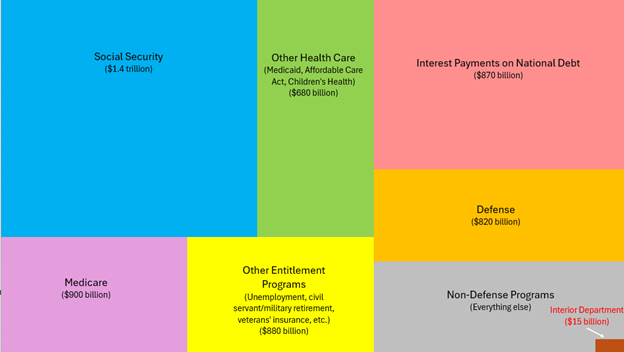

Mandatory spending programs comprised approximately 60 percent of federal spending in FY2024; Medicare and Social Security are the two largest mandatory spending programs, accounting for about 35 percent of total federal spending. Discretionary spending accounted for roughly another 27 percent, roughly divided equally between defense and non-defense programs, and interest payments on the national debt accounted for the remaining 13 percent (see chart, below).

During the campaign, President-elect Trump said he would not reduce Medicare and Social Security. In addition, it is widely believed that Republicans will seek to either increase, or at the least hold harmless, defense spending. Combined with debt payments, which must be expended by law, that would place approximately 62 percent of federal spending “off-limits” for budget cuts. That would mean significant reductions in spending would need to cone from other health care programs, like Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and from discretionary, non-defense programs that include everything from National Parks to housing aid to NASA and education.

Federal Spending in FY 2024

Federal spending is controlled by Congress, which under Article I, Section 9 is bestowed the sole power to enact laws that enable monies to be drawn from the Treasury. With fairly narrow margins in both chambers, it is unlikely that Congressional Republicans will try to cut spending to the degree that Musk and Ramaswamy have called for.

In their op-ed, however, the DOGE heads maintain that the President can refuse to spend money appropriated by Congress. In particular, they suggest the incoming administration cancel funding appropriated by Congress for programs that Congress did not authorize.

They cite the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) annual report of discretionary programs whose authorization has lapsed but for which Congress has appropriated funds. In fiscal year 2024, CBO identified $516 billion that Congress appropriated for 491 programs whose authorizations have expired.[i] These include programs across many agencies, and count among them (as cited by Musk and Ramaswamy) funding for Corporation for Public Broadcasting, grants to international organizations and groups like Planned Parenthood.

Efforts by a president to refuse to spend appropriated funds would conflict with the 1974 Impoundment Control Act, which requires the President to spend funds appropriated by Congress or seek Congressional approval to rescind specific funding; in other words, the law forces the Executive Branch to abide by Legislative Branch funding decisions. Musk and Ramaswamy state in their op-ed that “Mr. Trump has previously suggested this statute is unconstitutional, and we believe the current Supreme Court would likely side with him on this question.”[i]

It is possible, and perhaps likely, that President-elect Trump will try to challenge the Impoundment Control Act by rescinding federal spending, which would likely trigger a court case. Ultimately the Supreme Court would have to decide.

Musk and Ramaswamy also suggest the DOGE will identify “pinpoint executive actions” to reduce or eliminate waste, fraud and abuse from federal programs, including from entitlements like Medicare and Social Security. It is not clear how much money such actions, if they are within the President’s authority, will save.

Workforce

In the past, Ramasawmy has proposed cutting the federal workforce by 75 percent, while Musk has suggested he could eliminate 99 out of the 438 federal agencies that currently exist, with corresponding reduction in workforce.

In their op-ed, Musk and Ramaswamy said that they plan to reduce the federal workforce in a number of ways:

- Identifying “the minimum number of employees required at an agency for it to perform its constitutionally permissible and statutorily mandated functions.”[ii]

- Reducing the number of federal employes commensurate with a reduction in federal regulations; i.e., the fewer regulations on the book, the fewer employees will be needed to write and enforce them.

- Using existing laws to give federal workers “incentives for early retirement and to make voluntary severance payments to facilitate a graceful exit.”

In addition, Musk and Ramaswamy said they would recommend President-elect take additional steps – like relocating agencies out of Washington and requiring workers to return to the office five days a week – that would “would result in a wave of voluntary terminations.”[iii]

(The DOGE heads did not cite another Trump promise, to revive his Schedule F proposal to convert many civil service positions into at-will positions, which would enable him to terminate employees more easily and replace them with political appointees. Although Schedule F was revoked by President Biden, it is expected to return in the new Trump administration.)

The Musk-Ramaswamy workforce plans raise two questions: Do they accurately reflect the reality of the federal workforce and the real costs and benefits of such moves? And does the President have the authority to implement these plans?

On the first question, a number of critics have questioned some of Musk’s and Ramaswamy’s assumptions.

First, critics have pointed out that fewer regulations do not automatically translate into fewer workers, since the vast majority of federal workers do not write or enforce regulations. As Forbes writer Howard Gleckman noted, “the vast majority [of federal employees] distribute benefits or provide direct services to the public. Take the IRS. In fiscal year 2023, it had about 90,000 employees. Of those, less than 1 percent wrote regulations. By contrast, 20,000 staffers provided taxpayer services such as helping people file their returns.”[i]

In addition, despite their claims about the D.C.-centric nature of the federal workforce, the vast majority of federal employees do not work in the Washington metro area. According to the Washington Post, “Only 15 percent of the 2.19 million civilian full-time federal employees in the United States work in the Washington metro area, which includes Northern Virginia, suburban Maryland and even a touch of West Virginia. The other 85 percent work elsewhere around the country.”[ii]

Lastly, some critics question whether relocating federal agencies outside the Washington metropolitan area actually provides any workforce reductions or cost savings. As evidence, critics point to the 2019 relation of USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) and National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) to Kansas City. A large percentage of staff retired or left the civil service rather than relocate.

Subsequently, GAO found that, while ERS’s and NIFA’s workforce size and productivity temporarily declined following relocation, it “had largely recovered by September 2021. However, 2 years after the relocation, the agencies’ workforce was composed mostly of new employees with less experience at ERS and NIFA than the workforce prior to the relocation.”[iii]

Another study found that, despite claims by USDA that the relocation would save money, “the move to Kansas City will cost taxpayers between $83 and $182 million dollars, rather than saving them $300 million dollars.”[iv]

In other words, the USDA relocations cost taxpayers money and resulted in less institutional knowledge but no discernible reduction in the size of the federal workforce.

On the second question, whether the President has the authority to make such changes, the answers are murkier.

Musk and Ramaswamy argue that court decisions give the President wide authority to “prescribe rules governing the competitive service,” as long as they do not target specific employees. This would enable such moves as implementing return-to-office requirements and the reinstitution of Schedule F, which could directly and indirectly lead to reductions in the size of the workforce.

If the incoming administration wants to cut the workforce more directly without authorization from Congress, their options are somewhat limited.

Individual federal employees can be terminated for cause but must be provided 30 days’ notice and the opportunity to contest alleged misconduct prior to termination. Federal employees also have statutory whistleblower protections as well as civil rights protections on the basis of race, sex, age, gender, religion, disability status, or other protected class.[i]

The primary way the incoming administration could reduce the workforce is through a Reduction in Force (RIF) at one or more agencies. A RIF could lead to some workers losing their jobs and others being reassigned. Here, too, workers that are affected by a RIF have the right to appeal the decision. In addition, current Office of Personnel Management (OPM) rules require agencies to go through a detailed, formal process to institute a RIF – but the incoming administration could rewrite those rules to hasten the process.

The Executive Branch also could institute a Voluntary Early Retirement Authority (VERA), which provides incentives for federal workers to take early retirement. However, the rules governing VERA also are complex, and the number of actual reductions would depend on the number of employees opting to take advantage of the program.[ii]

It is expected that labor unions representing federal employees will aggressively work to prevent large-scale reductions in the workforce, largely through court action, but also by locking in collective bargaining agreements before January 20, 2025. As an example, the outgoing Biden administration recently agreed to a hybrid work deal for 42,000 Social Security Administration (SSA) employees represented by the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) through 2029.

Conclusion

Over the years, many Presidents have entered office looking to shrink the size of the federal government and make it more efficient. The record shows that most of these efforts had limited success or faded away as policymakers’ attention shifted to other priorities. DOGE may see the same fate.

That said, DOGE has some advantages over past efforts: Republicans control both the White House and Congress, giving them more power to effect change. And President-elect Trump has shown an affinity for pushing the envelope on assuming broad presidential powers. If the courts allow him to use those broad powers, at least some of the DOGE’s ideas could come to pass.

But the experiences of Trump’s first term – such as the effort to relocate federal agencies outside of Washington – show that reform efforts can also backfire, resulting in higher government spending for less benefit to taxpayers. Furthermore, if the DOGE recommends cuts to popular programs, the White House and Congressional Republicans could face voter backlash in the 2026 midterm elections.

References

[1] https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/marjorie-taylor-greene-head-new-doge-house-subcommittee/story?id=116138565

[1] https://bean.house.gov/media/press-releases/icymi-senator-ernst-joins-congressman-bean-creating-bicameral-doge-caucus

[1] https://www.npr.org/2024/12/05/nx-s1-5215817/democratic-rep-moskowitz-joins-trump-group-pushing-for-government-efficiency

[1] https://www.wsj.com/opinion/musk-and-ramaswamy-the-doge-plan-to-reform-government-supreme-court-guidance-end-executive-power-grab-fa51c020

[1] Ibid.

[1] Ibid.

[1] Ibid.

[1] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10172

[1] https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60580

[1] https://www.wsj.com/opinion/musk-and-ramaswamy-the-doge-plan-to-reform-government-supreme-court-guidance-end-executive-power-grab-fa51c020

[1] Ibid.

[1] Ibid.

[1] https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2024/11/26/what-trumps-doge-team-gets-wrong-about-the-federal-workforce/

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/27/where-do-federal-employees-live/

[1] https://www.gao.gov/assets/d23104709.pdf

[1] Report-MovingUSDAResearchersWillCostTaxpayers-AAEAReport2019june19final.docx.pdf

[1] https://www.fedelaw.com/federal-employee-termination-laws/#:~:text=You%20Need%20Today-,Can%20a%20Federal%20Employee%20Be%20Fired%3F,appeal%20period%2C%20and%20final%20action

[1] https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/workforce-restructuring/voluntary-early-retirement-authority/